Overview

Teaching: 60 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What are functions and how do I use them in C++?

Objectives

Learn how to structure code into functions.

Learn the syntax for declaring functions.

Learn about passing arguments to functions.

Functions enable programs to be broken into segments of code that perform individual tasks, and are the primary way of achieving structure and code reuse.

In C++, a function is a group of statements that is given a name, and which can be called from some point of the program. The most common syntax used to define a function is:

type name ( parameter1, parameter2, ...) { statements }

Where:

typeis the type of the value returned by the function.nameis the identifier by which the function can be called.parameters(as many as needed): Each parameter consists of a type followed by an identifier, with each parameter being separated from the next by a comma. Each parameter looks very much like a regular variable declaration (for example:int x), and in fact acts within the function as a regular variable which is local to the function. The purpose ofparametersis to allow passing arguments to the function from the location where it is called from.statementsis the function’s body. It is a block of statements surrounded by braces { } that specify what the function actually does.

Let’s have a look at an example:

// function example

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int addition(int a, int b)

{

int r;

r = a + b;

return r;

}

int main()

{

int z;

z = addition(5, 3);

cout << "The result is " << z << endl;

}

When this program is run, the result is:

The result is 8

This program is divided in two functions: addition and main. Remember that no matter which order functions are defined, a C++

program always starts by calling main. In fact, main is the only function called automatically, and the code in any other function

is only executed if its function is called from main (directly or indirectly).

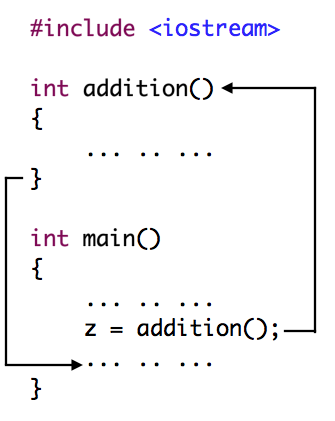

At the point at which the function addition is called from within main, control is passed to the new function. Further execution of

main is suspended, and will only resume once the addition function ends, as shown below:

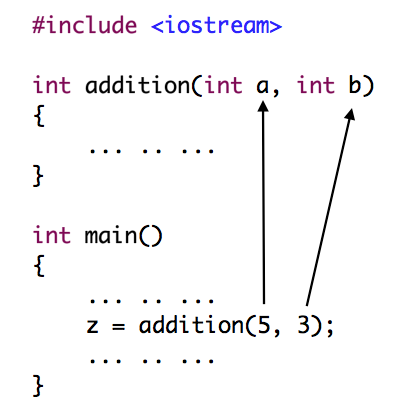

The parameters in the function declaration have a clear correspondence to the arguments passed in the function call. The call passes

two values to the function, and these correspond to the parameters a and b, declared for function addition. You can think of the

parameters as being variables that are accessible only within the function. At the moment of the function call, the value of both

arguments, 5 and 3, are assigned to variables a and b within the function, as show below:

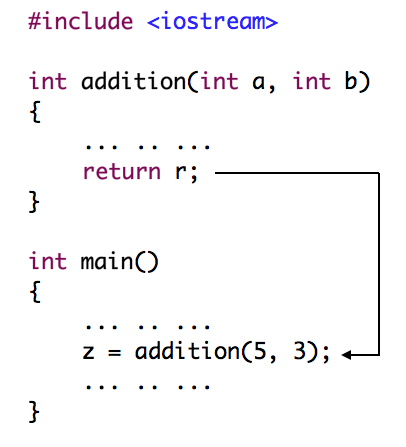

Inside the addition function, another variable r is declared, and is assigned the result of the expression a + b.

Since a has the value 5, and b the value 3, the result assigned to r will be 8.

The final statement within the function is return r;. This statement ends the function and returns the control back to the statement

immediately following the point where it was called, i.e. to function main. Because the addition function has a return type, the

call is evaluated as having a value, and this value is the value specified in the return statement that ended the function. This

results in the value, 8 being assigned to z in main as shown below:

Parameters and arguments

The term parameter (or sometimes formal parameter) is used to refer to the identifier used in the function definition, and that corresponds to a local variable used within the function.

The term argument is used to refer to the value (literal, variable, etc.) that is passed to the function via a function call, and that is matched to the corresponding parameter.

In many cases these terms are used interchangeably, but we will stick to the definitions here.

A function can be called multiple times within a program, and its argument is not limited just to literals:

// function example

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int subtraction(int a, int b)

{

int r;

r = a - b;

return r;

}

int main()

{

int x=5, y=3, z;

z = subtraction (7, 2);

cout << "The first result is " << z << endl;

cout << "The second result is " << subtraction (7, 2) << endl;

cout << "The third result is " << subtraction (x, y) << endl;

z= 4 + subtraction(x, y);

cout << "The fourth result is " << z << endl;

}

The result from running this program is:

The first result is 5

The second result is 5

The third result is 2

The fourth result is 6

This example defines a subtract function that simply returns the difference between its two parameters. This time, main calls this function

several times, demonstrating more possible ways in which a function can be called.

Let’s examine each of these calls, bearing in mind that each function call is itself an expression that is evaluated as the value it returns. You can think of it as if the function call was replaced by the returned value:

z = subtraction(7, 2);

cout << "The first result is " << z << endl;

If we replace the function call by the value it returns (i.e., 5), we would have:

z = 5;

cout << "The first result is " << z << endl;

Similarly for the statement:

cout << "The second result is " << subtraction(7, 2) << endl;

If we replace the function call by 5, we would have:

cout << "The second result is " << 5 << endl;

In this example, the arguments passed to subtraction are variables instead of literals:

cout << "The third result is " << subtraction (x,y) << endl;

The function is called with whatever the values of x and y are

at the moment of the call.

The fourth call is again similar:

z = 4 + subtraction(x, y);

The only change being that the function call is also an operand of an addition operation. Again, the result is the same as if the function call was replaced by its result: 6. Note, that thanks to the commutative property of additions, the above can also be written as:

z = subtraction(x, y) + 4;

This produces exactly the same result. Note also that the semicolon does not necessarily go after the function call, but is always at the end of the whole statement. Again, the logic behind may be easily seen again by replacing the function calls by their returned value:

z = 4 + 2; // same as z = 4 + subtraction (x,y);

z = 2 + 4; // same as z = subtraction (x,y) + 4;

Functions with no return type

The syntax we have used for declaring functions requires the declaration begin with a type. This is the type of the value returned by the function. What if the function does not need to return a value?

In this case, the function can be declared to return the type void. This is a special type to represent the

absence of value.

For example, a function that simply prints a message may not need to return any value:

// void function example

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void printmessage()

{

cout << "I'm a function!" << endl;

}

int main()

{

printmessage();

}

This results in:

I'm a function!

The void type can also be used in the function’s parameter list to explicitly specify that the function takes no actual parameters when called.

For example, printmessage could have been declared as:

void printmessage(void)

{

cout << "I'm a function!" << endl;

}

An empty parameter list can be used instead of void with same meaning.

The return value of main

You may have noticed that the return type of main (which is just a regular function) is int, but most examples in this and earlier lessons

did not actually return any value. This is because the compiler treats main differently from other functions, and will automatically include

an implicit return statement if one is not found. However, it is good practice to include a return statement at the end of main:

return 0;

When main returns zero (either implicitly or explicitly), it is interpreted by the environment that the program ended successfully. Other

values may be returned by main, and some environments use this value to indicate the result of the program execution.

However, this behavior is not required, nor portable, between platforms. The values for main that are guaranteed to be interpreted

in the same way on all platforms are as follows. Note that these values are defined in the header <cstdlib>:

| value | description |

|---|---|

| 0 | The program was successful |

| EXIT_SUCCESS | The program was successful (same as above). |

| EXIT_FAILURE | The program failed. |

Advanced Topics

Arguments passed by value and by reference

In the functions seen earlier, arguments have always been passed by value. This means that, when calling a function, what is passed to the function are the values of these arguments at the moment of the call, which are copied into the variables represented by the function parameters. For example, take:

int x=5, y=3, z;

z = addition(x, y);

In this case, function addition is passed 5 and 3, which are copies of the values of x and y, respectively. These values are

used to initialize variables defined as parameters in the function’s definition. However, any modification of these variables within the

function has no effect on the values of the variables x and y outside it.

In certain cases, it is useful to access an external variable from within a function. To do that, arguments can be passed by reference.

For example, the function duplicate in this code duplicates the value of its three arguments, causing the variables used as arguments

to actually be modified by the call:

// passing parameters by reference

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void duplicate(int& a, int& b, int& c)

{

a *= 2;

b *= 2;

c *= 2;

}

int main()

{

int x=1, y=3, z=7;

duplicate(x, y, z);

cout << "x=" << x << ", y=" << y << ", z=" << z << endl;

return 0;

}

When this program is run, the result is:

x=2, y=6, z=14

To gain access to its arguments, the function declares its parameters as references. In C++, references are indicated with an ampersand &

following the parameter type, as shown in the duplicate function in the example above.

When a variable is passed by reference, what is passed is no longer a copy, but the variable itself. The variable identified by the function parameter becomes a reference to the variable passed to the function, and any modification on their corresponding local variables within the function are reflected in the variables passed as arguments in the call.

In fact, a, b, and c become references to x, y, and z and any changes within the function is the same as actually modifying the

variable outside the function.

Efficiency considerations and const references

Calling a function with arguments passed by value causes copies of the values to be made. This is a relatively inexpensive operation for

fundamental types such as int, but if the parameter is a large compound type, it may result in significant overhead. For example, consider

the following function:

string concatenate(string a, string b)

{

return a + b;

}

This function takes two strings as parameters (by value), and returns the result of concatenating them. By passing the arguments by value,

the function forces a and b to be copies of the arguments passed to the function when it is called. If these are long strings, it may

mean copying large quantities of data just for the function call. By making these parameters pass by reference, this copying can

be eliminated:

string concatenate(string& a, string& b)

{

return a + b;

}

The function now operates directly on references to the strings passed as arguments, and, at most, it might mean the transfer of certain pointers to the function. In this regard, the version of concatenate taking references is more efficient than the version that passes by value.

On the flip side, functions with reference parameters are known as having side effects, since their arguments may be modified by the function. This is generally considered a programming practice to be avoided, since unexpected modification of arguments can lead to programming errors.

The solution to this issue is for the function to guarantee that its reference parameters are not going to be modified by the function. In C++, this is done by qualifying the parameters as constant:

string concatenate(const string& a, const string& b)

{

return a + b;

}

By doing this, the function is now forbidden to modify the values of a or b, but can still access their values as references, hence avoiding

the expensive copying.

In summary, const references provide functionality similar to passing arguments by value, but with an increased efficiency for

parameters of large types. That is why they are extremely popular in C++ for arguments of compound types. Note though,

that for most fundamental types, there is no noticeable difference in efficiency, and in some cases, const references may

even be less efficient!

Inline functions

Calling a function generally carries a certain overhead, and thus for very short functions, it may be more efficient to simply insert the code of the function where it is called, instead of performing the process of formally calling a function.

Preceding a function declaration with the inline specifier informs the compiler that inline expansion is preferred over the usual function

call mechanism for a specific function. This does not change the behavior of a function in any way, but is used to suggest that the

compiler should insert to function body at each point the function is called, instead of being invoked with a regular function call.

For example, the concatenate function above may be declared inline as:

inline string concatenate(const string& a, const string& b)

{

return a + b;

}

Note that most compilers already optimize code to generate inline functions when they see an opportunity to improve efficiency, even

if not explicitly marked with the inline specifier. Therefore, this specifier merely indicates the compiler that inline is preferred

for this function, although the compiler is free to not inline it, and optimize otherwise. In C++, optimization is a task delegated

to the compiler, which is free to generate any code for as long as the resulting behavior is the one specified by the code.

Default values in parameters

In C++, functions can also have optional parameters. An optional paramter is one for which no arguments are required in the call. Optional parameters are declared by specifying a default value for the last parameter, which is the value used by the function when called with fewer arguments. For example:

// default values in functions

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int divide(int a, int b=2)

{

int r;

r = a / b;

return r;

}

int main()

{

cout << divide(12) << endl;

cout << divide(20, 4) << endl;

return 0;

}

Running this code results in:

6

5

In this example, there are two calls to function divide. In the first one:

divide(12)

The call only passes one argument to the function, even though the function has two parameters. In this case, the function uses the default value of 2 for the second parameter. Therefore, the result is 6.

In the second call:

divide(20,4)

The call passes two arguments to the function. Therefore, the default value for the second parameter is ignored, and b takes the value

passed as argument, that is 4, yielding a result of 5.

Declaring functions

In C++, identifiers can only be used in expressions once they have been declared. For example, some variable x cannot be used before

being declared with a statement such as:

int x;

The same rule applies to functions. Functions cannot be called before they are declared. That is why, in all the previous examples of

functions, the functions were always defined in the file before the main function, which is the function from where the other functions

were called. If main were defined before the other functions, this would break the rule that functions shall be declared before being used,

and the code would not compile.

This rule can cause problems in certain situations however, such as when two functions call each other. In such a case, it is not possible for both functions to be declared before the other. To deal with this, C++ permits a prototype of the function to be declared without actually defining the function completely. The prototype provides just enough information so that the types involved in the function call are known. When using a prototype, the function still needs to be defined completely, but this can be later in the file.

A prototype declaration must include all types involved (the return type and the types of its arguments), using the same syntax as used in the definition of the function, but replacing the body of the function with an ending semicolon.

One difference is that the parameter list does not need to include the parameter names, but only their types. Parameter names can

nevertheless be specified, but they are optional, and do not need to necessarily match those in the function definition. For example,

a function called protofunction with two int parameters can be declared with either of these statements:

int protofunction (int first, int second);

int protofunction (int, int);

It is good practice to include a name for each parameter, however, as this improves the readability of the code.

This this example illustrates how functions can be declared before its definition:

// declaring functions prototypes

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void odd(int x);

void even(int x);

int main()

{

int i;

do {

cout << "Please, enter number (0 to exit): ";

cin >> i;

odd(i);

} while ( i!=0 );

return 0;

}

void odd(int x)

{

if ((x % 2) != 0) cout << "It is odd." << endl;

else even(x);

}

void even(int x)

{

if ((x % 2) == 0) cout << "It is even." << endl;

else odd (x);

}

Here is an example session using this program:

Please, enter number (0 to exit): 9

It is odd.

Please, enter number (0 to exit): 6

It is even.

Please, enter number (0 to exit): 1030

It is even.

Please, enter number (0 to exit): 0

It is even.

The following lines declare the prototype of the functions:

void odd(int a);

void even(int a);

These prototypes already contain all what is necessary to call the functions: the name, the types of their argument, and their return type

(void in this case).

Recursive functions

A recursive function is a function that calls itself. Some algorithms benefit from recursion, such as sorting elements, or calculating factorial numbers. For example, the mathematical formula for n! (factorial of n) is:

n! = n * (n-1) * (n-2) * (n-3) ... * 1

More concretely, 5! (factorial of 5) would be:

5! = 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 = 120

A recursive function is generally the simplest and most elegant way to calculate n! in C++:

// factorial calculator

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

long factorial(long a)

{

if (a > 1)

return (a * factorial (a-1));

return 1;

}

int main()

{

long number = 9;

cout << number << "! = " << factorial (number) << endl;

return 0;

}

The output from this program is:

9! = 362880

Notice how in function factorial there is a call to itself, but only if the argument passed was greater than 1. A condition like this is

essential in a recursive function since it is the only way to determine when to stop the recursion.

Key Points

Functions are the primary way to structure programs and achieve code reuse.

Execution can be transferred to a function, then resume at the point the function was invoked.

Functions can be supplied multiple values, but only return a single value.