Content from Part I: Introduction to Julia

Last updated on 2025-08-26 | Edit this page

Objectives

- Learn the basic infrastructure for programming in Julia

- Learn how to install packages and use them in the Julia REPL

Episodes

Content from Introduction

Last updated on 2025-08-29 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is Julia?

- Why use Julia?

Objectives

- Explain the difference between interpreted and compiled programming languages

- Compare how composing works in Julia and some common programming languages

What is a programming language?

A programming language mediates between the natural language of humans and the machine instructions of a computer. The human specifies what the computer should compute on a high level using the programming language. This specification will be translated to machine instructions, the so called assembly code, which will be executed by the processor (CPU, GPU, …).

Interpreting and compiling

This translation happens differently depending on the programming language you use. There are mainly two different techniques: compiling and interpreting. Interpreted languages such as Python and R translate instructions one at a time, while compiled languages like C and Fortran take whole documents, analyze the structure of the code, and perform optimizations before translating it to machine code.

This leads to more efficient machine instructions of the compiled code at the cost of less flexibility and more verbose code. Most prominently, compiled languages need an explicit type declaration for each variable.

Why Julia?

Just-in-Time (JIT) Compilation

Julia is a programming language that superficially looks like an interpreted language and mostly behaves like one. But before each function is executed it will be compiled just in time.

Thus you get the flexibility of an interpreted language and the execution speed of a compiled language at the cost of waiting a bit longer for the first execution of any function.

Built-in Engineering

Julia has software engineering features integrated into the language.

- dependency management

- packaging

- documentation

- testing

- profiling

Designed for Scientists

Julia includes many tools commonly used in scientific computing.

- multi-dimensional arrays

- linear algebra (including sparse arrays)

- random numbers

- statistics

(and, of course, many other things through easily-accessible packages).

Package Composition

There is another aspect of Julia that makes it interesting and that is the way packages compose. This is captured the best by an analogy from Sam Urmy:

Say you want a toy truck.

The Python/R solution is to look for the appropriate package–like buying a Playmobil truck. It comes pre-manufactured, well-engineered and tested, and does 95% of what you would ever want a toy truck to do.

The Fortran/C solution is to build the truck from scratch. This allows total customization and you can optimize the features and performance however you want. The downside is that it takes more time, you need woodworking skills, and might hurt yourself with the power tools.

The Julia solution is like Legos. You can get the truck kit if you want–which will require a bit more assembly than the Playmobil, but way less than building it from scratch. Or, you can get the component pieces and assemble the truck to your own specs. There’s no limit to what you can put together, and because the pieces all have the same system of bumps, everything snaps together quickly and easily.

OK, sure. Toy trucks are like linear algebra, though, a common request, and every “toy system” will have an implementation that works basically fine. But what if you want a time-traveling sailing/space ship with lasers AND dragon wings? And it should be as easy to build and use as a basic dump truck?

There’s a reason that only Lego ever made anything like Dr. Cyber’s Flying Time Vessel!

Originally posted on Discourse.

- Julia is a just-in-time compiled language

- Julia packages compose well

- Designed for science and engineering

Content from Using the REPL

Last updated on 2025-08-29 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to use the REPL?

Objectives

- Explore basic functionality of input.

- Learn how to declare variables.

- Learn about REPL modes.

Entering the REPL

Melissa and her classmates open a terminal and launch

julia:

_

_ _ _(_)_ | Documentation: https://docs.julialang.org

(_) | (_) (_) |

_ _ _| |_ __ _ | Type "?" for help, "]?" for Pkg help.

| | | | | | |/ _` | |

| | |_| | | | (_| | | Version 1.11.6 (2025-07-09)

_/ |\__'_|_|_|\__'_| | Official https://julialang.org/ release

|__/ |

julia>This is the so-called REPL, which stands for read-evaluate-print loop. The interactive command-line REPL allows quick and easy execution of Julia statements.

Like the terminal, the Julia REPL has a prompt, where it awaits input:

implicit prompt

Most of the code boxes that follow do not show the

julia> prompt, even though it’s there in the REPL.

Why?

It’s important to delineate input (what you type) and output (how the machine responds). The prompt can be confusing, so it is excluded. You may assume that any Julia box prepends the prompt on each line of input.

Visual Studio Code

An alternative to using the REPL through a terminal is to work with

Visual Studio Code or its open source altenative

VSCodium. VSC is a source code editor for which a julia

extension is available. After installing the application, simply click

on the “Extension” symbol on the left side and search for

julia. Once installed julia remains usable and

can be selected as a programming language in new documents.

For further guidance and visual aid, check out the provided video!

Variables

The first thing they try is to perform basic arithmetic operations:

OUTPUT

30.2That works as expected. It is also possible to bind a name to a value

via the assignment operator =, which makes it easier to

refer to the value later on. These names are called

variables.

OUTPUT

60.4Melissa notices that assignment also returns the value. She can also check which variables are defined in the current session by running

OUTPUT

name size summary

–––––––––––– ––––––– –––––––

Base Module

Core Module

Main Module

distance 8 bytes Float64

distance_x_2 8 bytes Float64Unicode

In Julia, Unicode characters are also allowed as variables like

α = 2. Unicode characters can be entered by a backslash

followed by their LaTeX

name and then pressing tab (in this case

\alphatab).

REPL Modes

Help Mode

Unfortunately Melissa can’t remember the LaTeX name of ∂ so she copies the character , presses ? for help mode,

pastes the ∂ character, then presses enter:

OUTPUT

"∂" can be typed by \partial<tab>Great! This way she can easily look up the names she needs. She gets back to normal mode by pressing backspace.

Exploring Julia’s Help Mode

Help mode can also be used to look up the documentation for Julia

functions. Use Julia’s help mode to read the documentation for the

varinfo() function.

Shell Mode

Another useful mode is the shell mode that can be entered by pressing ;. The prompt has now changed:

Shell mode can be used to issue commands to the underlying shell, but don’t confuse it with an actual shell: special shell syntax like piping won’t work. Like before, hit backspace to get back to the Julia prompt.

Hello, shell>

(pwd and cd) !

Two commonly used shell commands are pwd

(print working

directory) and cd (change

directory).

- Use

pwdto find out what is your current working directory. - Type the command

cdin shell mode, which by default will bring you to your “home directory”. - Use

pwdagain. Did you get a different result from before? Why or why not?

The working directory is the location from which you launched Julia.

To navigate to a different directory, you can use the cd

command by entering: cd <directory>. By default, this

command will return you to your home directory if a specific directory

is not given. If you initially launched Julia from your home directory,

the working directory remains unchanged, so the output of the second

pwd command will be identical to the first. Conversely, if

you were in a different directory when you started Julia, the results of

the two pwd commands will differ. You can use

cd - to go back to your previous location.

Hello, shell>

(ls)!

Another useful shell command is ls (list

files). Use it to show the contents of your home directory.

Hello, shell>

(nano and cat)!

Use the shell mode to create a file called hello.jl with

the nano terminal text editor. Inside that file write the simple hello

world program print("Hello World!").

Check the content of the file using cat hello.jl and

then run the program using julia hello.jl.

include

The include function executes the code from a file in

the current context. Let’s modify the previous challenge to illustrate

this.

Challenge

Edit the file hello.jl to print the value of a variable

x with print("Hello, ", x) (use

?print if you’re curious). Define x in the

REPL and include hello.jl to use the variable.

Before we move on let’s delete the file we created:

- The REPL will

- Read the given input

- Evaluate the given expression

- Print the result to the user

- Loop back to the prompt again

- Pressing ? enters help mode.

- Pressing ; enters shell mode.

- Pressing ] enters pkg mode.

- To exit shell, help or pkg mode, hit backspace.

Content from The Julia Type System

Last updated on 2025-08-29 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is the use of types?

- How are types organized in Julia?

Objectives

- Understand the structure of the type tree.

- Know how to traverse the type tree.

- Know how to build mutable and immutable types.

Structuring variables

Melissa wants to keep the variables corresponding to the trebuchet

(counterweight, release_angle) separate from

the variables coming from the environment (wind,

target_distance). That is why she chooses to group them

together using structures. There are two structure types:

- immutable structures, whose fields can not be changed after creation

- keyword:

struct

- keyword:

- mutable structures, whose fields can change after creation

- keyword:

mutable struct

- keyword:

Since Melissa wants to change the parameters of the trebuchet, she

uses a mutable struct for it. But she cannot influence the

environment and thus uses a struct for those values.

Types and hierarchy

Here ::Float64 is a type specification, indicating that

this variable should be a 64-bit floating point number, and

:: is an operator that is read

“is an instance of.” If Melissa hadn’t specified the type, the variables

would have the type Any by default.

In Julia every type can have only one supertype, so let’s count how

many types are between Float64 and Any:

1.

OUTPUT

AbstractFloat2.

OUTPUT

Real3.

OUTPUT

Number4.

OUTPUT

AnySo we have the relationship

Float64 <: AbstractFloat <: Real <: Number <: Any

where <:

is the subtype operator, used here to mean the item on the

left “is a subtype of” the item on the right.

Float64 is a concrete type, which means that

you can actually create objects of this type. For example

1.0 is an object of type Float64. We can check

this at the REPL using either (or both) the typeof function

or the isa

operator:

OUTPUT

Float64or

OUTPUT

trueAll the other types are abstract types that are used to

address groups of types. For example, if we declare a variable as

a::Real then it can be bound to any value that is a subtype

of Real.

Let’s quickly check what are all the subtypes of

Real:

OUTPUT

4-element Vector{Any}:

AbstractFloat

AbstractIrrational

Integer

RationalThis way the types form a tree with abstract types on the nodes and

concrete types as leaves. Have a look at this visualization of all

subtypes of Number:

The correct answer is 4: while 1 is an integer,

1.0 is a floating-point value.

Instances

So far Melissa only defined the layout of her new types

Trebuchet and Environment. To actually create

a value of this type she has to call the so called constructor,

which is a function with the same name as the corresponding type and as

many arguments as there are fields.

OUTPUT

Trebuchet(500.0, 0.7853981633974483)Note how the values will get converted to the specified field type.

OUTPUT

Environment(5.0, 100.0)trebuchet is called an instance or

object of the type Trebuchet. There can only ever

be one definition of the type Trebuchet but you can create

many instances of that type with different values for its fields.

Since the type Trebuchet was defined as a

mutable struct, the instance trebuchet can be

changed.

OUTPUT

1.2566370614359172OUTPUT

Trebuchet(500.0, 1.2566370614359172)The instance environment cannot, however, since the type

Environment is immutable.

ERROR

ERROR: setfield!: immutable struct of type Environment cannot be changed

Stacktrace:

[...]A Little More about Types

Let’s look at an example of a parametric type:

Vector{T}. The braces indicate the parameter(s). The name

Vector without the parameter is a special type of abstract

type called a UnionAll. That’s because the parameter is

needed to specify a concrete type.

OUTPUT

UnionAllOUTPUT

DataTypeOUTPUT

(Vector, DenseVector, AbstractVector, Any)OUTPUT

(Vector{Float64}, DenseVector{Float64}, AbstractVector{Float64}, Any)Type constraints

You can see two “dimensions” of abstraction here, the hierarchy and the parameter. Remember abstract types represent “groups” of types that are intuitively similar. This is useful when defining structures or functions that need to be generic. When you need your function to apply to a group of possible input types, you simply think in terms of how tight the constraint needs to be.

Don’t change a variable’s type

While a variable that is specified to be an abstract type can change types within that constraint, it is best to avoid changing the type of a local variable, especially in places that are performance-critical.

Creating a subtype

A concrete type can be made a subtype of an abstract type with the

subtype operator <:. Since

Trebuchet contains several fields that are mutable Melissa

thinks it is a good idea to make it a subtype of

AbstractVector.

Caveat: Redefining Structs

JULIA

mutable struct Trebuchet <: AbstractVector{Float64}

counterweight::Float64

release_angle::Float64

endERROR

ERROR: invalid redefinition of constant Main.Trebuchet

Stacktrace:

[1] top-level scope

@ REPL[9]:1This error message is clear: you’re not allowed to define a

struct using a name that’s already in use.

Restart the REPL

In Julia it is not very easy to redefine a struct. It is

necessary to restart the REPL to define the new definition of

Trebuchet, or take a different name instead.

Melissa decides to keep going and come back to this later.

- In Julia types have only one direct supertype.

Content from Using the Package Manager

Last updated on 2025-09-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- Where do I find packages?

- How do I add packages?

- How can I use packages?

Objectives

- Learn to add packages using pkg-mode

- Learn to resolve name conflicts

- Learn to activate environments

The Package Manager

The package manager

This chapter focuses on the package mode available within the REPL.

A different approach would be using the Pkg package in

regular Julia code.

If you prefer to use that method and want to know more, remember how to get help.

(e.g., ?Pkg.add)

Now it is time for Melissa and their mates to simulate the launch of

the trebuchet. The necessary equations are really complicated, but an

investigation on JuliaHub revealed

that someone already implemented these and published it as the Julia

package Trebuchet.jl.

That saves some real work.

Melissa enters package mode by pressing ]:

The julia> prompt becomes a blue pkg>

prompt that shows the Julia version that Melissa is running.

After consulting the documentation she knows that the prompt is showing the currently activated environment and that this is the global environment that is activated by default.

However, she doesn’t want to clutter the global environment when

working on her project. The default global environment is indicated with

(@v1.x) before the pkg> prompt, where

x is the minor version number of julia, so on julia 1.11 it

will look like (@v1.11). To create a new environment she

uses the activate function of the package manager:

OUTPUT

Activating new project at `~/projects/trebuchet`In this environment she adds the Trebuchet package from

its open source code repository on GitHub

by typing

Melissa quickly recognizes that far more packages are being installed

than just Trebuchet. These are the dependencies of

Trebuchet. From the output

OUTPUT

[...]

Updating `[...]/projects/trebuchet/Project.toml`

[98b73d46] + Trebuchet v#.#.#

Updating `[...]/projects/trebuchet/Manifest.toml`

[1520ce14] + AbstractTrees v#.#.#

[79e6a3ab] + Adapt v#.#.#

[...]she sees that two files were created: Project.toml and

Manifest.toml.

The project file Project.toml only contains the packages

needed for her project, while the manifest file

Manifest.toml records the direct and indirect dependencies

as well as their current version, thus providing a fully reproducible

record of the code that is actually executed. “That is really handy when

I want to share my work with the others,” thinks Melissa.

After the installation finished she can check the packages present in her environment.

OUTPUT

Status `~/projects/trebuchet/Project.toml`

[98b73d46] Trebuchet v0.2.2

Why use GitHub?

Melissa could have added the GitHub version of Trebuchet.jl by typing

In this case the JuliaHub version is the same as the GitHub version, so Melissa does not need to specify the installation.

If you know a package is stable, go ahead and install the default version registered on JuliaHub. Otherwise, it’s good to check how different that version is from the current state of the software project. Click through the link under “Repository” on the JuliaHub package page.

Using and importing packages

Now that Melissa added the package to her environment, she needs to

load it. Julia provides two keywords for loading packages:

using and import.

The difference is that import brings only the name of

the package into the namespace and then all functions in that package

need the name in front (prefixed). But packages can define a list of

function names to export, which means the functions should be brought

into the user’s namespace when he loads the package with

using. This makes working at the REPL more convenient.

Name conflicts

It may happen that name conflicts arise. For example Melissa defined

a structure named Trebuchet, but the package she added to

the environment is also named Trebuchet. Now she would get

an error if she tried to import/using it

directly. One solution is to assign a nickname or alias to the package

upon import using the keyword as:

- Find packages on JuliaHub

- add packages using

pkg> add - use many small environments rather than one big environment

Content from Part II: Programming in Julia

Last updated on 2025-09-17 | Edit this page

Objectives

- Learn to write functions

- Learn how interfaces work

- Learn basic control flow structures

Episodes

Content from Write functions!

Last updated on 2025-09-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do I call a function?

- Where can I find help about using a function?

- What are methods?

Objectives

- Usage of positional and keyword arguments

- Defining named and anonymous functions

- Reading error messages

Working with functions

Now that Melissa successfully installed the package she wants to figure out what she can do with it.

Julia’s Base module offers a handy function for

inspecting other modules called names. Let’s look at its

docstring; remember that pressing ? opens the

help?> prompt:

OUTPUT

names(x::Module; all::Bool = false, imported::Bool = false)

Get a vector of the public names of a Module, excluding deprecated names. If

all is true, then the list also includes non-public names defined in the

module, deprecated names, and compiler-generated names. If imported is true,

then names explicitly imported from other modules are also included. Names

are returned in sorted order.

As a special case, all names defined in Main are considered "public", since

it is not idiomatic to explicitly mark names from Main as public.In Julia we have two types of arguments: positional and keyword, separated by a semi-colon.

- Positional arguments are determined by their position and thus the order in which arguments are given to the function matters.

- Keyword arguments are passed as a combination of the keyword and the value to the function. They can be given in any order, but they need to have a default value.

Function Parameters

Let’s take a closer look at the signature of the names

function:

It takes three arguments:

-

x, a positional argument of typeModule, followed by a; -

all, a keyword argument of typeBoolwith a default value offalse -

imported, anotherBoolkeyword argument that defaults tofalse

Suppose Melissa wanted to get all names of the

Trebuchets module, including those that are not exported.

What would the function call look like?

names(Trebuchets, true)-

names(Trebuchets, all = true) names(Trebuchets, all)-

names(Trebuchets; all = true) - Both 2 and 4

- Both arguments are present, but

trueis presented without a keyword. This throws aMethodError: no method matching names(::Module, ::Bool) - This is a correct call.

- Two arguments are present, but the keyword

allis not assigned a value. This throws aMethodError: no method matching names(::Module, ::typeof(all)) - This is also correct: you can specify

where the positional arguments end with the

;, but you do not have to. - This is the most correct answer.

Before starting to work in a new document, Melissa has to:

- Activate her environment

OUTPUT

Activating project at `~/projects/trebuchet`- Import the package under its modified name

- Define the structures

JULIA

mutable struct Trebuchet <: AbstractVector{Float64}

counterweight::Float64

release_angle::Float64

end

struct Environment

wind::Float64

target_distance::Float64

endNow she can execute

OUTPUT

6-element Vector{Symbol}:

:Trebuchet

:TrebuchetState

:run

:shoot

:simulate

:visualisewhich yields the exported names of the Trebuchets

module. By convention types are named with CamelCase while

functions typically have snake_case. Since Melissa is

interested in simulating shots, she looks at the shoot

function from Trebuchets (again, using ?):

OUTPUT

shoot(ws, angle, w)

shoot((ws, angle, w))

Shoots a Trebuchet with weight w in kg. Releases the weight at the release

angle angle in radians. The current wind speed is ws in m/s.

Returns (t, dist), with travel time t in s and travelled distance dist in m.Generic functions and methods

In the output we see that shoot has two different

argument signatures: one with three arguments and one with a

Tuple of three elements as its single argument. These two

signatures correspond to two different implementations. In our case one

is calling the other.

Functions of the same name with different argument signatures are

called methods of a generic function of that name. In

our example we have two methods of the shoot generic

function.

Almost all function in Julia are generic functions and in particular

all user defined functions. An example with particularly many methods is

+. You can list its methods by executing

methods(+), for example.

Julia determines which method to apply to a tuple of arguments according to set of rules, which are documented in the Julia Manual’s Methods section.

Now she is ready to fire the first shot.

OUTPUT

(Trebuchet.TrebuchetState(Trebuchet.Lengths{Float64}(1.524, 2.0702016, 0.5334, 0.6096, 2.0826984, 0.8311896, 0.037947600000000005), Trebuchet.Masses{Float64}(226.796185, 0.14877829736, 4.8307587405), Trebuchet.Angles{Float64}(-0.4328124904398228, 1.1928977546511481, 1.437218009822302), Trebuchet.AnglularVelocities{Float64}(-6.80709816163242, 10.240657933288563, -22.420510883318446), Trebuchet.Constants{Float64}(5.0, 1.0, 1.0, 9.80665, 0.7853981633974482), Trebuchet.Inertias{Float64}(0.042140110093804806, 2.7288719786342384), Val{:End}(), 60.0, Trebuchet.Vec(114.88494815382731, -1.5239999999999991), Trebuchet.Vec(10.886295450427806, -21.290442812748466), Solution(387) , 3.943408301947865, Val{:Released}()), 114.88494815382731)That is a lot of output, but Melissa is actually only interested in the distance, which is the second element of the tuple that was returned. So she tries again and grabs the second element this time:

OUTPUT

114.88494815382731which means the shot traveled approximately 115 m.

Defining functions

Melissa wants to make her future work easier and she fears she might forget to take the second element. That’s why she puts it together in a function like this:

JULIA

function shoot_distance(windspeed, angle, weight)

Trebuchets.shoot(windspeed, angle, weight)[2]

endOUTPUT

shoot_distance (generic function with 1 method)Implicit return

Note that Melissa didn’t have to use the return keyword,

since in Julia the value of the last line will be returned by default.

But she could have used an explicit return and the function would behave

the same.

Now Melissa can just call her wrapper function:

OUTPUT

114.88494815382731Adding methods

Since Melissa wants to work with the structs Trebuchet

and Environment, she adds another convenience method for

those:

JULIA

function shoot_distance(trebuchet::Trebuchet, env::Environment)

shoot_distance(env.wind, trebuchet.release_angle, trebuchet.counterweight)

endOUTPUT

shoot_distance (generic function with 2 methods)This method will call the former method and pass the correct fields

from the Trebuchet and Environment

structures.

Slurping and splatting

By peeking into the documentation,

Melissa discovers that she doesn’t need to explicitly declare all the

input arguments. Instead she can slurp the arguments in the

function definition and splat them in the function body using

three dots (...) like this:

OUTPUT

shoot_distance (generic function with 3 methods)Anonymous functions

Sometimes it is useful to have a new function and not have to come up with a new name. These are anonymous functions. They can be defined with either the so-called stabby lambda notation,

OUTPUT

#1 (generic function with 1 method)or in long form, by omitting the name:

OUTPUT

#3 (generic function with 1 method)Calling methods

Now that she defined all these methods she tries calling a few

OUTPUT

114.88494815382731OUTPUT

114.88494815382731For the other method she needs to construct Trebuchet

and Environment objects first

OUTPUT

Environment(5.0, 100.0)ERROR

MethodError: no method matching size(::Trebuchet)

Closest candidates are:

size(::AbstractArray{T, N}, !Matched::Any) where {T, N}

@ Base abstractarray.jl:42

size(!Matched::Union{LinearAlgebra.QR, LinearAlgebra.QRCompactWY, LinearAlgebra.QRPivoted})

@ LinearAlgebra /opt/hostedtoolcache/julia/1.9.4/x64/share/julia/stdlib/v1.9/LinearAlgebra/src/qr.jl:582

size(!Matched::Union{LinearAlgebra.QR, LinearAlgebra.QRCompactWY, LinearAlgebra.QRPivoted}, !Matched::Integer)

@ LinearAlgebra /opt/hostedtoolcache/julia/1.9.4/x64/share/julia/stdlib/v1.9/LinearAlgebra/src/qr.jl:581

...

Errors and finding documentation

This error tells her two things:

- a function named

sizewas called - it didn’t have a method for

Trebuchet

Melissa wants to add the missing method to size but she

doesn’t know where it is defined. There is a handy macro named

@which that obtains the module where the function is

defined.

Macros

Macro names begin with @ and they don’t need parentheses

or commas to delimit their arguments. Macros can transform any valid

Julia expression and are quite powerful. They can be expanded by

prepending @macroexpand to the macro call of interest.

OUTPUT

BaseNow Melissa knows she needs to add a method to Base.size

with the signature (::Trebuchet).

She can also lookup the docstring using the @doc

macro

OUTPUT

size(A::AbstractArray, [dim])

Return a tuple containing the dimensions of A. Optionally you can specify a

dimension to just get the length of that dimension.

Note that size may not be defined for arrays with non-standard indices, in

which case axes may be useful. See the manual chapter on arrays with custom

indices.

See also: length, ndims, eachindex, sizeof.

Examples

≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡

julia> A = fill(1, (2,3,4));

julia> size(A)

(2, 3, 4)

julia> size(A, 2)

3

size(cb::CircularBuffer)

Return a tuple with the size of the buffer.

With that information she can now implement this method:

But that is a 3 lines of text for a very short definition. Melissa can also using the short form notation to fit this in a single line:

Omitting unneeded arguments

Melissa could also name the argument in the signature. Like this:

(trebuchet::Trebuchet), but since the argument is not

needed to compute the output of the function she can omit it. The

argument is in this case only used to dispatch to the correct

method.

Now she can try again

ERROR

CanonicalIndexError: getindex not defined for TrebuchetAgain, there is an error but this time the error message is

different: It’s no longer a method for size that is missing

but for getindex. She looks up the documentation for that

function

OUTPUT

getindex(type[, elements...])

Construct a 1-d array of the specified type. This is usually called with the

syntax Type[]. Element values can be specified using Type[a,b,c,...].

Examples

≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡

julia> Int8[1, 2, 3]

3-element Vector{Int8}:

1

2

3

julia> getindex(Int8, 1, 2, 3)

3-element Vector{Int8}:

1

2

3

getindex(collection, key...)

Retrieve the value(s) stored at the given key or index within a collection.

The syntax a[i,j,...] is converted by the compiler to getindex(a, i, j, ...).

See also get, keys, eachindex.

Examples

≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡

julia> A = Dict("a" => 1, "b" => 2)

Dict{String, Int64} with 2 entries:

"b" => 2

"a" => 1

julia> getindex(A, "a")

1

getindex(A, inds...)

Return a subset of array A as selected by the indices inds.

Each index may be any supported index type, such as an Integer,

CartesianIndex, range, or array of supported indices. A : may be used to

select all elements along a specific dimension, and a boolean array (e.g. an

Array{Bool} or a BitArray) may be used to filter for elements where the

corresponding index is true.

When inds selects multiple elements, this function returns a newly allocated

array. To index multiple elements without making a copy, use view instead.

See the manual section on array indexing for details.

Examples

≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡

julia> A = [1 2; 3 4]

2×2 Matrix{Int64}:

1 2

3 4

julia> getindex(A, 1)

1

julia> getindex(A, [2, 1])

2-element Vector{Int64}:

3

1

julia> getindex(A, 2:4)

3-element Vector{Int64}:

3

2

4

julia> getindex(A, 2, 1)

3

julia> getindex(A, CartesianIndex(2, 1))

3

julia> getindex(A, :, 2)

2-element Vector{Int64}:

2

4

julia> getindex(A, 2, :)

2-element Vector{Int64}:

3

4

julia> getindex(A, A .> 2)

2-element Vector{Int64}:

3

4

getindex(tree::GitTree, target::AbstractString) -> GitObject

Look up target path in the tree, returning a GitObject (a GitBlob in the case

of a file, or another GitTree if looking up a directory).

Examples

≡≡≡≡≡≡≡≡

tree = LibGit2.GitTree(repo, "HEAD^{tree}")

readme = tree["README.md"]

subtree = tree["test"]

runtests = subtree["runtests.jl"]

observable[]

Returns the current value of observable.

getindex(A::ArrayPartition, i::Colon, j...)

Returns the entry at index j... of every partition of A.

getindex(A::ArrayPartition, ::Colon)

Returns a vector with all elements of array partition A.

getindex(

c::SciMLBase.AbstractClock,

idx

) -> SciMLBase.IndexedClock

Return a SciMLBase.IndexedClock representing the subset of the time points

that the clock ticked indicated by idx.

v = sd[k]

Argument sd is a SortedDict and k is a key. In an expression, this retrieves

the value (v) associated with the key (or KeyError if none). On the left-hand

side of an assignment, this assigns or reassigns the value associated with the

key. (For assigning and reassigning, see also insert! below.) Time: O(c log n)

cb[i]

Get the i-th element of CircularBuffer.

• cb[1] to get the element at the front

• cb[end] to get the element at the back

getindex(tree, ind)

Gets the key present at index ind of the tree. Indexing is done in increasing

order of key.

Note that the documentation for all methods gets shown and Melissa needs to look for the relevant method first. In this case its the paragraph starting with

getindex(A, inds...)After a bit of pondering the figures it should be enough to add a

method for getindex with a single number.

getindex(trebuchet::Trebuchet, i::Int)Syntactic sugar

| Short syntax | Equivalent function |

|---|---|

| a[1] | getindex(a, 1) |

| a[2] = 3.0 | setindex!(a, 3.0, 2) |

| a.b | getproperty(a, :b) |

| a.b = 4.0 | setproperty!(a, :b, 4.0) |

- You can think of functions being a collection of methods

- Methods are defined by their signature

- The signature is defined by the number of arguments, their order and their type

- Keep the number of positional arguments low

- Macros transform Julia expressions

Content from Interfaces & conditionals

Last updated on 2025-09-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to use conditionals?

- What is an interface?

Objectives

- Writing conditionals

- Understanding interfaces

Conditionals

Before starting to work in a new document, Melissa has to:

- Activate her environment

OUTPUT

Activating project at `~/projects/trebuchet`- Import the package under its modified name

- Define the structures

JULIA

mutable struct Trebuchet <: AbstractVector{Float64}

counterweight::Float64

release_angle::Float64

end

struct Environment

wind::Float64

target_distance::Float64

end

Base.size(::Trebuchet) = tuple(2)Now that Melissa knows that she has to add a method for

getindex(trebuchet::Trebuchet, i::Int)she thinks about the implementation.

If the index is 1 she wants to get the

counterweight field and if the index is 2 she

wants to get release_angle and since these are the only two

fields she wants to return an error if anything else comes in. In Julia

the keywords to specify conditions are if,

elseif and else, closed with an

end.

Thus she writes

JULIA

function Base.getindex(trebuchet::Trebuchet, i::Int)

if i === 1

return trebuchet.counterweight

elseif i === 2

return trebuchet.release_angle

else

error("Trebuchet only accepts indices 1 and 2, yours is $i")

end

endAnd tries again:

OUTPUT

2-element Trebuchet:

500.0

0.7853981633974483Notice, that the printing is different from our

trebuchet in the

former episode.

Interfaces

Why is that? By subtyping Trebuchet as

AbstractVector we implicitly opted into a widespread

interface in the Julia language: AbstractArrays.

An interface is a collection of methods that should be implemented by

all subtypes of the interface type in order for generic code to work.

For example, the Julia

manual lists all methods that a subtype of

AbstractArray need to implement to adhere to the

AbstractArray interface:

-

size(A)returns a tuple containing the dimensions ofA -

getindex(A, i::Int)returns the value associated with indexi -

setindex!(A, v, i::Int)writes a new valuevat the indexi(optional)

Now, that Melissa implemented the mandatory methods for this

interface for the Trebuchet type, it will work with every

function in Base that accepts an

AbstractArray. She tries a few things that now work without

her writing explicit code for it:

OUTPUT

2-element Vector{Float64}:

1000.0

1.5707963267948966OUTPUT

250000.61685027508OUTPUT

2×2 Matrix{Float64}:

250000.0 392.699

392.699 0.61685That is, it now behaves like you would expect from an ordinary matrix.

Now she goes about implementing the missing optional method for

setindex! of the AbstractArray interface.

Implement setindex!

Write the missing method for

setindex!(trebuchet::Trebuchet, v, i::Int) similar to

Melissas getindex function.

With the new Trebuchet defined with a complete

AbstractArray interface, Melissa tries her new method to

modify a counterweight by index:

OUTPUT

2OUTPUT

2-element Trebuchet:

2.0

0.7853981633974483- Conditions use

if,elseif,elseandend - Interfaces are informal

- Interfaces facilitate code reuse

Content from Loops

Last updated on 2025-09-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What are for and while loops?

- What is a comprehension?

Objectives

- Writing loops

- Exposure to other language and library features

Before starting to work in a new document, Melissa has to:

- Activate her environment

OUTPUT

Activating project at `~/projects/trebuchet`- Import the package under its modified name

- Define the structures

JULIA

mutable struct Trebuchet <: AbstractVector{Float64}

counterweight::Float64

release_angle::Float64

end

struct Environment

wind::Float64

target_distance::Float64

end

Base.size(::Trebuchet) = tuple(2)

function Base.getindex(trebuchet::Trebuchet, i::Int)

if i === 1

return trebuchet.counterweight

elseif i === 2

return trebuchet.release_angle

else

error("Trebuchet only accepts indices 1 and 2, yours is $i")

end

end

function Base.setindex!(trebuchet::Trebuchet, v, i::Int)

if i === 1

trebuchet.counterweight = v

elseif i === 2

trebuchet.release_angle = v

else

error("Trebuchet only accepts indices 1 and 2, yours is $i")

end

end

function shoot_distance(trebuchet::Trebuchet, env::Environment)

shoot_distance(env.wind, trebuchet.release_angle, trebuchet.counterweight)

end

function shoot_distance(args...) # slurping

Trebuchets.shoot(args...)[2] # splatting

endOUTPUT

shoot_distance (generic function with 2 methods)Now Melissa knows how to shoot the virtual trebuchet and get the distance of the projectile, but in order to aim she needs to take a lot of trial shots in a row. She wants her trebuchet to only shoot a hundred meters.

She could execute the function several times on the REPL with different parameters, but that gets tiresome quickly. A better way to do this is to use loops.

Random search

The first thing that comes to her mind is to randomly sample points

of the parameter space of the trebuchet. The function

rand() will give her a random number between 0 and 1 that

is uniformly distributed. So

OUTPUT

2-element Trebuchet:

228.38576259167743

1.0428133782844782will give her a Trebuchet with a weight between 0 and 500 and a release angle between 0 and pi/2 radians at random.

Now she can store the results of 3 random trebuchets in an array like this

JULIA

env = Environment(5, 100)

distances = [shoot_distance(Trebuchet(rand() * 500, rand() * pi / 2), env) for _ in 1:3]OUTPUT

3-element Vector{Float64}:

75.81435701587722

83.01842049268829

67.14411448705451This is called an array comprehension. To get the information of the parameters and the results in one place she writes that again a bit differently

JULIA

N = 10

weights = [rand() * 500 for _ in 1:N]

angles = [rand() * pi/2 for _ in 1:N]

distances = [(w,a) => shoot_distance(Trebuchet(w, a), env) for (w, a) in zip(weights, angles)]OUTPUT

10-element Vector{Pair{Tuple{Float64, Float64}, Float64}}:

(3.3334597480246253, 0.7838682352298685) => 0.6815707596179541

(210.78228935379622, 1.381946534840864) => 35.85286633327975

(401.5993709331619, 0.2185755446723246) => 96.9029165112703

(174.8500444474639, 1.3802675063026215) => 34.83498096430634

(459.5195474131575, 0.6388081196321991) => 117.62925382680423

(325.9792258612826, 1.4742042308383514) => 23.118879918525415

(424.04535348026496, 0.13367159006587603) => 84.32898973441384

(367.203106692998, 0.6088354356429886) => 117.46105246416498

(12.984772128024124, 1.5235451260228559) => 0.6815707596179541

(10.485349585032166, 0.6353974863672037) => 0.6815707596179541Gradient descent

That is working out so far, but Melissa wonders if she can improve her parameters more systematically.

Digression: Gradients

The shoot_distance function takes three input parameters

and returns one value (the distance). Whenever we change one of the

input parameters, we will get a different distance.

The gradient of a function gives the direction in which the return value will change when each input value changes.

Since the shoot_distance function has three input

parameters, the gradient of shoot_distance will return a

3-element Array: one direction for each input

parameter.

Thanks to automatic

differentiation and the Julia package ForwardDiff.jl

gradients can be calculated easily.

Melissa uses the gradient function of

ForwardDiff.jl to get the direction in which she needs to

change the parameters to make the largest difference.

Do you remember?

What does Melissa need to write into the REPL to install the package

ForwardDiff?

] install ForwardDiffadd ForwardDiff] add ForwardDiff.jl-

] add ForwardDiff

JULIA

using ForwardDiff: gradient

imprecise_trebuchet = Trebuchet(500.0, 0.25pi);

environment = Environment(5.0, 100.0);

grad = gradient(x ->(shoot_distance([environment.wind, x[2], x[1]])

- environment.target_distance),

imprecise_trebuchet)OUTPUT

2-element Vector{Float64}:

-0.12516519503998055

-49.443442438172205Melissa now changes her arguments a little bit in the direction of the gradient and checks the new distance.

JULIA

better_trebuchet = imprecise_trebuchet - 0.05 * grad;

shoot_distance([5, better_trebuchet[2], better_trebuchet[1]])OUTPUT

-2.785549535224487Great! That didn’t shoot past the target, but instead it landed a bit too short.

Experiment

How far can you change the parameters in the direction of the gradient, such that it still improves the distance?

JULIA

better_trebuchet = imprecise_trebuchet - 0.04 * grad

shoot_distance([environment.wind, better_trebuchet[2], better_trebuchet[1]])

120.48753521261001JULIA

better_trebuchet = imprecise_trebuchet - 0.03 * grad

shoot_distance([environment.wind, better_trebuchet[2], better_trebuchet[1]])

107.80646596787481JULIA

better_trebuchet = imprecise_trebuchet - 0.02 * grad

shoot_distance([environment.wind, better_trebuchet[2], better_trebuchet[1]])

33.90699307740854JULIA

better_trebuchet = imprecise_trebuchet - 0.025 * grad

shoot_distance([environment.wind, better_trebuchet[2], better_trebuchet[1]])

75.87613276409223Looks like the “best” trebuchet for a target 100 m away will be between 2.5% and 3% down the gradient from the imprecise trebuchet.

For loops

Now that Melissa knows it is going in the right direction she wants

to automate the additional iterations. She writes a new function

aim, that performs the application of the gradient

N times.

JULIA

function aim(trebuchet, environment; N = 5, η = 0.05)

better_trebuchet = copy(trebuchet)

for _ in 1:N

grad = gradient(x -> (shoot_distance([environment.wind, x[2], x[1]])

- environment.target_distance),

better_trebuchet)

better_trebuchet -= η * grad

end

return Trebuchet(better_trebuchet[1], better_trebuchet[2])

end

better_trebuchet = aim(imprecise_trebuchet, environment);

shoot_distance(environment.wind, better_trebuchet[2], better_trebuchet[1])OUTPUT

-2.2195176928658915Explore

Play around with different inputs of N and

η. How close can you come?

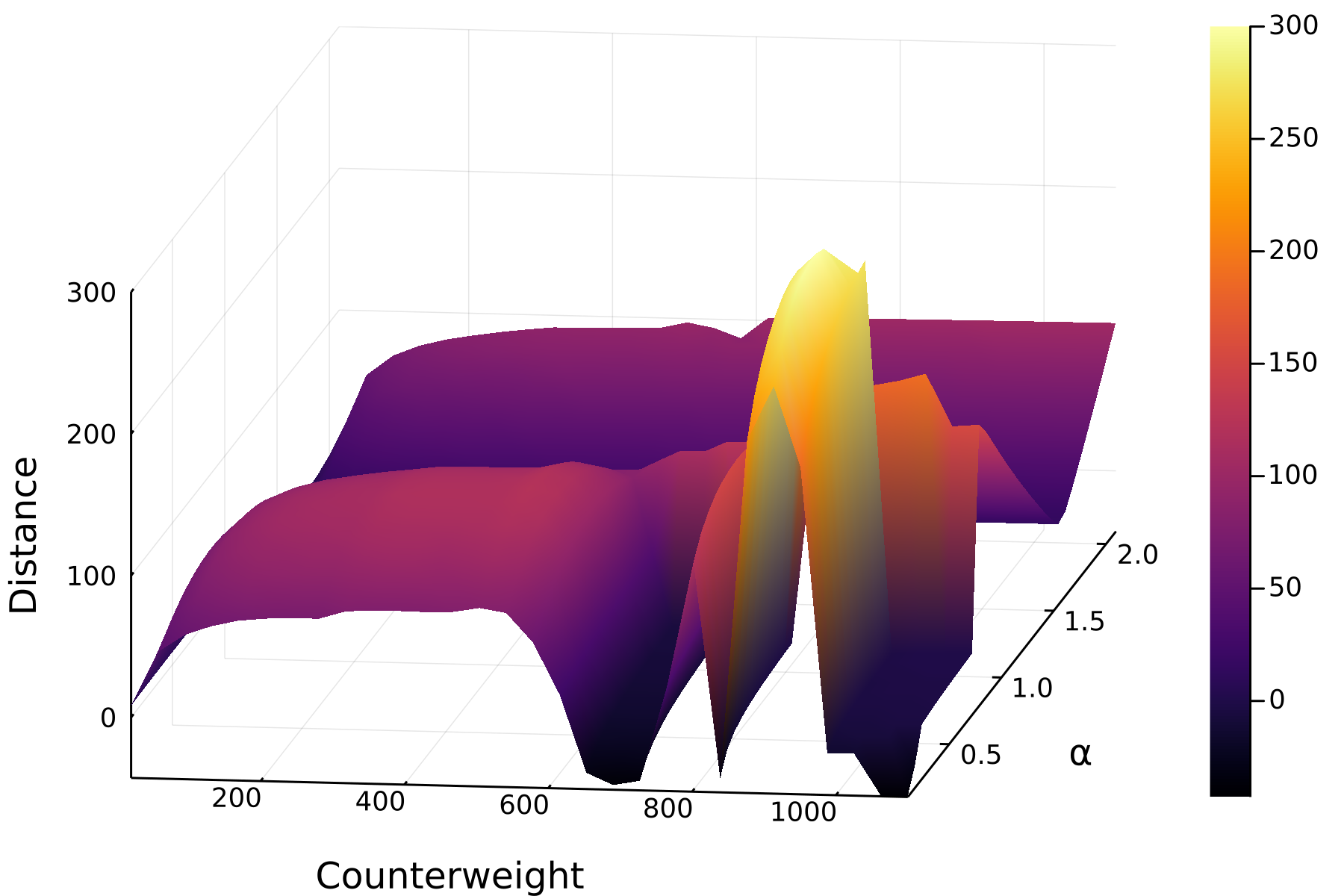

This is a highly non-linear system and thus very sensitive. The

distances across different values for the counterweight and the release

angle α look like this:

Aborting programs

If a call takes too long, you can abort it with

Ctrl-c

While loops

Melissa finds the output of the above aim function too

unpredictable to be useful. That’s why she decides to change it a bit.

This time she uses a while-loop to run the iterations until

she is sufficiently near her target.

(Hint: ε is

\epsilontab, and η is

\etatab.)

JULIA

function aim(trebuchet, environment; ε = 0.1, η = 0.05)

better_trebuchet = copy(trebuchet)

hit = x -> (shoot_distance([environment.wind, x[2], x[1]]) - environment.target_distance)

while abs(hit(better_trebuchet)) > ε

grad = gradient(hit, better_trebuchet)

better_trebuchet -= η * grad

end

return Trebuchet(better_trebuchet[1], better_trebuchet[2])

end

better_trebuchet = aim(imprecise_trebuchet, environment);

shoot_distance(better_trebuchet, environment)OUTPUT

100.05601729579894That is more what she had in mind. Your trebuchet may be tuned differently, but it should hit just as close as hers.

- Use for loops for a known number of iterations and while loops for an unknown number of iterations.

Content from Part III: Managing Julia Projects

Last updated on 2025-09-17 | Edit this page

Objectives

- Learn how modules work

- Learn how to create a package

- Learn basic built-in testing tools

Episodes

Content from Using Modules

Last updated on 2025-09-17 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What’s the purpose of modules?

Objectives

- Structure your code using modules

- Use Revise.jl to track changes

Modules

Melissa now has a bunch of definitions in her running Julia session and using the REPL for interactive exploration is great, but it is more and more taxing to keep in mind what is defined, and all the definitions are lost once she closes the REPL.

That is why she decides to put her code in a file. She opens up her

text editor and creates a file called aim_trebuchet.jl in

the current working directory and pastes the code she got so far in

there. This is what it looks like:

JULIA

using Pkg

Pkg.activate("projects/trebuchet")

import Trebuchet as Trebuchets

using ForwardDiff: gradient

mutable struct Trebuchet <: AbstractVector{Float64}

counterweight::Float64

release_angle::Float64

end

Base.size(trebuchet::Trebuchet) = tuple(2)

Base.getindex(trebuchet::Trebuchet, i::Int) = getfield(trebuchet, i)

function Base.setindex!(trebuchet::Trebuchet, v, i::Int)

if i === 1

trebuchet.counterweight = v

elseif i === 2

trebuchet.release_angle = v

else

error("Trebuchet only accepts indices 1 and 2, yours is $i")

end

end

struct Environment

wind::Float64

target_distance::Float64

end

function shoot_distance(args...)

Trebuchets.shoot(args...)[2]

end

function shoot_distance(trebuchet::Trebuchet, env::Environment)

shoot_distance(env.wind, trebuchet.release_angle, trebuchet.counterweight)

end

function aim(trebuchet::Trebuchet, environment::Environment; ε = 1e-1, η = 0.05)

better_trebuchet = copy(trebuchet)

hit = x -> (shoot_distance([environment.wind, x[2], x[1]]) - environment.target_distance)

while abs(hit(better_trebuchet)) > ε

grad = gradient(hit, better_trebuchet)

better_trebuchet -= η * grad

end

return Trebuchet(better_trebuchet[1], better_trebuchet[2])

end

imprecise_trebuchet = Trebuchet(500.0, 0.25pi)

environment = Environment(5, 100)

precise_trebuchet = aim(imprecise_trebuchet, environment)

shoot_distance(precise_trebuchet, environment)Now Melissa can run include("aim_trebuchet.jl") in the

REPL to execute her code.

She also recognizes that she has a bunch of definitions at the beginning that she doesn’t need to execute more than once in a session and some lines at the end that use these definitions which she might run more often. She will split these in two separate files and put the definitions into a module. The module will put the definitions into their own namespace which is the module name. This means Melissa would need to put the module name before each definition if she uses it outside of the module. But she remembers from the Using the package manager Episode that she can export names that don’t need to be prefixed.

She names her module MelissasModule and accordingly the

file MelissasModule.jl. From this module she exports the

names aim, shoot_distance,

Trebuchet and Environment. This way she can

leave her other code unchanged.

JULIA

module MelissasModule

using Pkg

Pkg.activate("projects/trebuchet")

import Trebuchet as Trebuchets

using ForwardDiff: gradient

export aim, shoot_distance, Trebuchet, Environment

mutable struct Trebuchet <: AbstractVector{Float64}

counterweight::Float64

release_angle::Float64

end

Base.size(trebuchet::Trebuchet) = tuple(2)

Base.getindex(trebuchet::Trebuchet, i::Int) = getfield(trebuchet, i)

function Base.setindex!(trebuchet::Trebuchet, v, i::Int)

if i === 1

trebuchet.counterweight = v

elseif i === 2

trebuchet.release_angle = v

else

error("Trebuchet only accepts indices 1 and 2, yours is $i")

end

end

struct Environment

wind::Float64

target_distance::Float64

end

function shoot_distance(args...)

Trebuchets.shoot(args...)[2]

end

function shoot_distance(trebuchet::Trebuchet, env::Environment)

shoot_distance(env.wind, trebuchet.release_angle, trebuchet.counterweight)

end

function aim(trebuchet::Trebuchet, environment::Environment; ε = 1e-1, η = 0.05)

better_trebuchet = copy(trebuchet)

hit = x -> (shoot_distance([environment.wind, x[2], x[1]]) - environment.target_distance)

while abs(hit(better_trebuchet)) > ε

grad = gradient(hit, better_trebuchet)

better_trebuchet -= η * grad

end

return Trebuchet(better_trebuchet[1], better_trebuchet[2])

end

end # MelissasModuleThe rest of the code goes to a file she calls

MelissasCode.jl.

JULIA

using .MelissasModule

imprecise_trebuchet = Trebuchet(500.0, 0.25pi)

environment = Environment(5, 100)

precise_trebuchet = aim(imprecise_trebuchet, environment)

shoot_distance(precise_trebuchet, environment)Now she can include MelissasModule.jl once, and change

and include MelissasCode.jl as often as she wants. But what

if she wants to make changes to the module? If she changes the code in

the module, re-includes the module and runs her code again, she only

gets a bunch of warnings, but her changes are not applied.

Revise.jl

Revise.jl is a package that can keep track of changes in

your files and load these in a running Julia session.

Melissa needs to take two things into account:

-

using Revisemust come beforeusingany Package that she wants to be tracked - she should use

includetinstead ofincludefor included files (tfor “tracking”)

Thus she now runs

JULIA

using Revise

includet(joinpath(path,"MelissasModule.jl"))

include(joinpath(path,"MelissasCode.jl"))OUTPUT

100.05601729579894where path is the path to her files.

and any change she makes in MelissasModule.jl will be

visible in the next run of her code.

Did I say any changes?

Well, almost any. Revise can’t track changes to structures.

- Modules introduce namespaces

- Public API has to be documented and can be exported

Content from Creating Packages

Last updated on 2025-09-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How to create a package?

Objectives

- Learn setting up a project using modules

- Learn common package structure

- Learn to browse GitHub or juliahub for packages and find documentation

Melissa is now confident that her module is fine and she wants to make it available for the rest of her physics club. She decides to put it in a package. This way she can also locally use Julia’s package manager for managing her module.

From project to package

The path from having a module to having a package is actually very

short: Packages need a name and a uuid field

in their Project.toml.

A UUID is a universally unique

identifier. Thankfully Julia comes with the

UUIDs package, that can generate uuids for

Melissa via UUIDs.uuid4().

In addition Melissa needs to have a specific directory structure. She

looks at the example package Example.jl

which has the following structure:

├── docs

│ ├── make.jl

│ ├── Project.toml

│ └── src

│ └── index.md

├── LICENSE.md

├── Project.toml

├── README.md

├── src

│ └── Example.jl

└── test

└── runtests.jlMake it a package

You can open your Project.toml and add

name = <your name>,

uuid = <your uuid> and optionally an

authors field, each on a separate line.

The basic src structure can be generated with a complete

Project.toml using the generate command from

Pkg. Melissa enters pkg mode using ].

OUTPUT

Generating project MelissasModule:

projects/MelissasModule/Project.toml

projects/MelissasModule/src/MelissasModule.jl

Melissa’s new package directory structure looks like this.

├── Project.toml

└── src

└── MelissasModule.jlShe opens the newly generated Project.toml to see the

contents (The uuid and authors fields will be

unique to you:

name = "MelissasModule"

uuid = "..."

authors = ["..."]

version = "0.1.0"Melissa knows she needs the Trebuchet and

ForwardDiff packages as dependencies. She activates her new

project and adds them:

OUTPUT

Activating project at `~/projects/MelissasModule`OUTPUT

Resolving package versions...

Compat entries added for Trebuchet, ForwardDiff

Updating `~/projects/MelissasModule/Project.toml`

[f6369f11] + ForwardDiff v1.2.1

[98b73d46] + Trebuchet v0.2.2

Updating `~/projects/MelissasModule/Manifest.toml`

[...]The Project.toml now has entries for those

dependencies:

name = "MelissasModule"

uuid = "..."

authors = ["..."]

version = "0.1.0"

[deps]

ForwardDiff = "f6369f11-7733-5829-9624-2563aa707210"

Trebuchet = "98b73d46-197d-11e9-11eb-69a6ff759d3a"

[compat]

ForwardDiff = "1.2.1"

Trebuchet = "0.2.2"The generated source file src/MelissasModule.jl looks

like this:

Melissa replaces the greet() function with the contents

of her module she created earlier (except for the two lines using

Pkg; there is no need to activate another

project now that her module is part of a project with those

dependencies).

Now Melissa can use

instead of needing to includet MelissasModule.jl, and

she can write using MelissasModule instead of

using .MelissasModule. She modifies

MelissasCode.jl accordingly.

Register a package

In order for her friends to be able to get the package, Melissa registers the package in the general registry. This can be done either via JuliaHub or by making a pull request on GitHub which can also be automated by the Julia Registrator.

Creating a new package

Melissa thinks next time she will start with a package right away.

Browsing the packages she found PkgTemplates.jl and PkgSkeleton.jl which makes setting up the typical folder structure very easy.

Create your own package

Look at the documentation of the package creation helper packages and

create a new package using generate.

- The general registry is hosted on GitHub.

- Packaging is easy

Content from Adding tests

Last updated on 2025-09-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What are unit tests?

- How are tests organized in Julia?

Objectives

- Learn to create unit tests and test sets using the

Teststandard library

Unit tests

Now that Melissa has released her first package she fears that future changes will impact the existing functionality of her package. This can be prevented by adding tests to her package.

Looking at the structure of other packages Melissa figured out that

tests usually go in a separate test folder next to the

src folder. This should contain a runtests.jl

file.

The standard library Test provides the functionality for

writing tests: namely, the macros @test and

@testset.

@test can be used to test a single equality, such as

OUTPUT

Test PassedSeveral tests can be grouped in a test set with a descriptive name

OUTPUT

Test.DefaultTestSet("Test arithmetic equalities", Any[], 1, false, false, true, 1.731669987513481e9, 1.731669987543832e9, false)Melissa sees that she can run her package tests using the pkg mode of the REPL:

ERROR

ERROR: Package MelissasModule did not provide a `test/runtests.jl` file

Remember from earlier that the conventional project structure

included a test/runtests.jl file? This file is the entry

point for package tests.

Test environment

Melissa needed to add Test to her package in order to

run the code above, but actually Test is not needed for her

package other than testing. Melissa needs to generate a testing

environment with its own dependencies:

OUTPUT

Activating new project at `~/projects/MelissasModule/test`

OUTPUT

Resolving package versions...

Updating `~/projects/MelissasModule/test/Project.toml`

[8dfed614] + Test v1.11.0

Updating `~/projects/MelissasModule/test/Manifest.toml`

[2a0f44e3] + Base64 v1.11.0

[b77e0a4c] + InteractiveUtils v1.11.0

[56ddb016] + Logging v1.11.0

[d6f4376e] + Markdown v1.11.0

[9a3f8284] + Random v1.11.0

[ea8e919c] + SHA v0.7.0

[9e88b42a] + Serialization v1.11.0

[8dfed614] + Test v1.11.0

Now Melissas project structure looks like this:

MelissasModule/

├── Project.toml

├── src

│ └── MelissasModule.jl

└── test

└── Project.tomlAnd the test/Project.toml has:

[deps]

Test = "8dfed614-e22c-5e08-85e1-65c5234f0b40"

Using just one Project.toml

Alternatively, Melissa could include the Test package as

an “extra” in her top-level Project.toml and require that

dependency for the test target.

Check out the Project.toml from the Example.jl project for an example of this.

Challenge

Create a test for MelissasModule in test/runtests.jl

Create a test that ensures that shoot_distance returns a

value that is between target - ε and

target + ε.

JULIA

using MelissasModule

using Test

@testset "Test hitting target" begin

imprecise_trebuchet = Trebuchet(500.0, 0.25pi)

environment = Environment(5, 100)

precise_trebuchet = aim(imprecise_trebuchet, environment)

final_distance = shoot_distance(precise_trebuchet, environment)

@test 100 - 0.1 <= final_distance <= 100 + 0.1

# default ε is 0.1

# could also use:

# @test abs(final_distance - 100) <= 0.1

endNow Melissa can run this test from pkg mode:

OUTPUT

Testing MelissasModule

Status `/tmp/jl_TTQJwg/Project.toml`

[34b7a6fa] MelissasModule v0.1.0 `~/projects/MelissasModule`

[8dfed614] Test v1.11.0

Status `/tmp/jl_TTQJwg/Manifest.toml`

[...]

⋮

# Skipping output here setting up the temporary testing environment

⋮

Testing Running tests...

Test Summary: | Pass Total Time

Test hitting target | 1 1 19.7s

Testing MelissasModule tests passed

- Tests are important